On the different schools of Goju-ryu.

by Ryan Gregory, February 11th, 2012As a distinct martial art, karate-do (“empty hand way”) originated in Okinawa, in what was the Ryukyu Kingdom until it was annexed by Japan and became a prefecture in 1879. However, its roots extend much deeper into the past and make their way to early martial arts from China. It is only much more recently that karate moved from Okinawa to Japan, and subsequently to the rest of the world. Indeed, the specific styles of karate that we now recognize mostly originated in the first half of the 20th century.

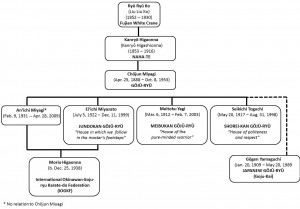

The style of karate that I have studied in the past and recently returned to is Goju-ryu, or “hard-soft style”. It was created by Chojun Miyagi, who had been trained in Nahe-te (a fighting style endemic to Naha city) by Kanryo Higaonna, who in turn had trained in Chinese fighting arts including White Crane boxing from the Fujian province of China, which he studied under Ryu Ryu Ko.

There are plenty of histories of Okinawan karate and other martial arts available, so I won’t go into any more detail beyond the simplified story given above. For the purposes of this post, and for my training more broadly, I am interested in the distinctions that exist within the single style of Goju-ryu karate-do.

Chojun Miyagi died in 1953, and did not formally name a successor to the Goju-ryu style. There is controversy amongst some Goju-ryu practicioners in terms of who the rightful successor was and, by extension, which of his students best preserved the “true” Goju-ryu developed by the master.

I don’t think this is a question that can be settled easily, given the limited historical data available. And, in fact, I don’t think it’s particularly important in the larger picture. There are some notable differences in details among the styles developed and taught by Chojun Miyagi’s top students, but fundamentally I believe they all capture the core of the Goju-ryu style as it was orginally developed. The fact that two students who trained for many years with Chojun Miyagi could perform the same kata slightly differently is pretty compelling evidence that there is no single “true” Goju-ryu anymore, and perhaps there never was only one way to practice the style.

Within modern Goju-ryu, there are four main schools. Three of these stem directly from dojos opened in Okinawa by former students of Chojun Miyagi and as such they remain quite similar to each other. Of course, we would expect there to be some differences — the founders of these schools were masters in their own right, and each had something valuable to contribute to the further development of the style. The fourth, which I won’t discuss much here, is often referred to as “Japanese Goju-ryu” to distinguish it from the Okinawan schools. It was founded by Gogen Yamaguchi, who trained with Chojun Miyagi (and some of his students) for only a short period of time. As the story goes, Miyagi tasked Yamaguchi with spreading Goju-ryu in Japan, but I am not aware of documentation that shows this to be the case. We do know that Yamaguchi claimed to have been given a 10th-dan rank by Miyagi, but it is known that Miyagi never granted dan ranks to anyone. Whatever the case, Japanese Goju-ryu has become very popular, and Yamaguchi can be credited with bringing the style to the rest of the world.

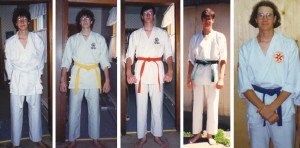

When I first began training as an undergraduate student, the style happened to be Japanese Goju-ryu. Later, I began training in Okinawan Goju-ryu and ultimately I decided (as a green belt) not to return to the campus club but rather to continue training at the dojo in my hometown in the Okinawan style. One of the most notable differences between Okinawan and Japanese Goju-ryu is that the latter tends to include flashier, more exaggerrated movements. I found it hard to imagine going back to that after learning more about the original style developed by Chojun Miyagi and the reason for small, efficient movements.

Now, back to the three main schools of Okinawan Goju-ryu. These are Jundokan, which was founded by Eiichi Miyazato; Shorei-kan, started by Seikichi Toguchi; and Meibukan, developed by Meitoku Yagi. Again, these literally represented different schools — new dojos opened by Miyagi’s pupils after his death. Jundokan (“House in which we follow in the master’s footsteps”) was the form of Okinawan Goju-ryu in which I trained previously. I am currently training in Meibukan (“House of the pure-minded warrior”). Unfortunately, I know little about Shorei-kan (“House of politeness and respect”), but I will spend some time on this blog discussing what I learn are differences between Jundokan and Meibukan Goju-ryu. I have already seen quite a few, but again, these tend to be relatively minor overall and it is not the case that one is correct and the other incorrect. By way of analogy, they are akin to regional dialects rather than being like the use of correct vs. incorrect grammar.

So, what are some of the differences between Jundokan and Meibukan Goju-ryu? Here are some initial observations:

1) Differences in walking basics. In Jundokan, the middle block (chudan uke) was different from the low block (gedan uke). For those who know what I am talking about, the middle block in Jundokan is the one used in Gekisai ichi. In Meibukan, they’re both basically gedan uke but the stance differs. Also, in Meibukan we do not include side kicks (yoko geri), roundhouse kicks (mawashi geri), or back kicks (ushiro geri) in walking basics, only front kicks (mae geri). However, we do practice these other kicks in bag work. There is also a shuto block in Meibukan that is new to me that was absent in the Jundokan walking basics.

2) Differences in kata order. This is one of the big differences, as shown in the table below.

| Belt | Jundokan | Meibukan |

| White | Geki Sai Ichi | Sanchin |

| Yellow | Geki Sai Ni | Geki Sai Ichi |

| Orange | Sanchin Ichi Bassai Dai |

Geki Sai Ni Tenchi |

| Green | Saifa Ten U No Kon (Bo) |

Saifa Tensho |

| Blue | Seienchin | Shi Sho Shin Seiryu |

| Brown | Sanchin Ni | Sanseiru Byakko |

| Shodan | Shi Sho Shin | Sesan Shuzzaku |

| Nidan | Sanseiru | Seienchin |

| Sandan | Sepai | Sepai Genbu |

| Yondan | Kururunfa | Kururunfa |

| Godan | Sesan | Suparinpe |

Having trained in Jundokan, I am missing some kata that are learned earlier in Meibukan (e.g., Tensho, Shi Sho Shin), but I also learned Seienchin as a blue belt whereas this is a 2nd-dan black belt kata in Meibukan.

3) Differences in Sanchin kata. In Jundokan, there are two versions of Sanchin kata. Sanchin Ichi is learned as an orange belt and does not include any turns. It’s three steps forward and three steps back. This version was developed by Chojun Miyagi, though sources differ as to why he altered the kata. For example, some suggest that in his later years he was confined to sitting in a chair while his students trained, and they had to perform the kata without turning their backs on him. I don’t think this makes much sense, because most of the other kata involve turning as well. Another story is that Miyagi demonstrated the kata for the Emperor of Japan, and had to change it so as not to turn his back at any stage. Whatever the explanation, this version of the kata is learned first and later the more complex Sanchin Ni, which is the kata taught to Miyagi by Kanryo Higaonna, is a brown belt kata. In Meibukan, there is only one Sanchin kata (the original version with the turns), and it is learned right at the white belt level. Luckily for me, I learned Sanchin Ni as a brown belt, so it’s familiar. Historically, I think Sanchin was taught early by Miyagi to his students and they had to work on it for several years before learning another kata (and which one they learned next varied from student to student). Note, however, that these students were training every day for several hours rather than for an hour twice per week. Sanchin is fundamental to all schools of Okinawan Goju-ryu, but whether one learns it early (as was done in Miyagi’s school) or later (i.e., when a student is more likely to understand it and execute it properly) is probably incidental in the long run. Still, it’s interesting to see white belts in Meibukan being taught what is a brown belt kata in Jundokan.

4) Differences in additional kata. This is another significant difference. Meitoku Yagi, the founder of Meibukan Goju-ryu, developed a series of kata that are unique to the school. Having only recently begun training in Meibukan, I obviously do not know any of them, but I have seen some performed. They appear to be more heavily inspired by Chinese arts, emphasizing softer, circular movements. I understand that they are also complementary, in that the attack moves in one correspond to the defensive moves in another. They’re very intriguing, and I look forward to learning them in due course. On the other hand, there were some non-Goju kata required in my Jundokan dojo that are not part of the Meibukan syllabus. The afore-mentioned Sanchin Ichi, for example, but also Bassai Dai (a Shotokan kata) and a bo kata (Ten U No Kon), which were required for green and blue belt, respectively. I’m working on remembering these kata even though they aren’t part of the school in which I am now training.

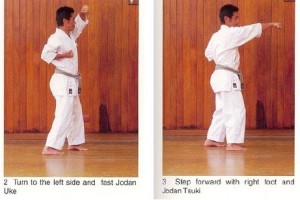

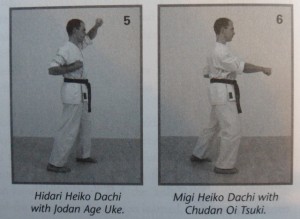

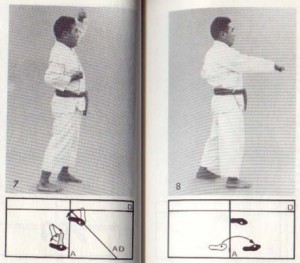

5) Differences in some moves within kata. There are noticeable differences even in the first moves of one of the first kata. In Gekisai ichi and Gekisai ni, there is a high block and then a punch in the opening moves. In Jundokan, this is a high punch whereas in Meibukan and Shorei-kan it is a middle punch. The moves with a kiai also differ. In Jundokan, the kiai are on the reverse punches. In Meibukan, they are on the kicks and the shutos.

Gekisai ichi performed with a high punch as in Jundokan. Image from the book Okinawa Den Gojuryu Karate-do by Eiichi Miyazato.

Gekisai ichi performed with a middle punch as in Meibukan. Image from the book Karate Goju Ryu Meibukan by Lex Opdam.

Gekisai ichi, performed with a middle punch as in Shorei-kan. Image from the book Okinawan Goju Ryu: The Fundamentals of Shorei-kan Karate by Seikichi Toguchi.

There are some more subtle differences as well, such as the way cat stance (neko ashi dachi) is performed, in some of the moves in Saifa (e.g., a jump into the kick position in Meibukan), and the inclusion of a small attack move at the very end of Sanchin that is not done in the Jundokan kata.

It’s very nice to be back in a dojo, and I am certainly enjoying the opportunity to learn another slightly different variant of Okinawan Goju-ryu. Thankfully it is very similar in general to what I had learned before, but there are also enough distinctions to keep it especially interesting. I’ll share more of these as I discover them.

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Kodokan Judo

Kodokan Judo