The evolution and essence of Goju-ryu karate.

by Ryan Gregory, June 4th, 2015(This is a brief overview of the history of Goju-ryu that was required as part of my recent black stripe grading. Given the format, it is obviously just a simplified summary of a much more complex history. Nevertheless, I think it might be of some interest, so I am re-posting it here. The main point I wanted to make is that we cannot, nor should we want to, preserve a single version of a style that has always been evolving.)

Introduction: the rise of Ryukyuan martial arts

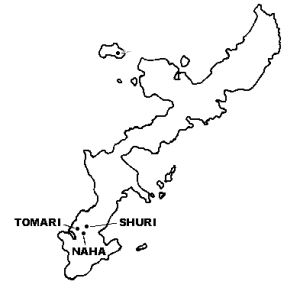

The Ryukyu Islands represent an archipelago of more than 100 volcanic islands located south of Japan, extending southwest nearly the entire distance from the southern Japanese island of Kyushu to Taiwan (Figure 1). The largest of these islands, Okinawa, is roughly equidistant from Japan to the north and China to the west, and has long been the political and cultural centre of the Ryukyu Island system. Today, the Ryukyu Islands are part of the Japanese prefecture of Okinawa, having been formally annexed in 1879. However, for centuries prior to this, there existed an independent Ryukyu Kingdom that maintained strong economic and cultural ties with several of its neighbours, most notably China.

Figure 1. The Ryukyu Islands, an archipelago consisting of more than 100 small islands located between Japan and Taiwan of the coast of China. The largest island in the chain, Okinawa, is the original home of karate.

As part of an ongoing cultural exchange, a large number of Chinese families (traditional sources put the number at 36) were sent from Fujian Province in China to settle in Okinawa around 1392. These families brought with them various aspects of Chinese culture, including knowledge of traditional Chinese martial arts. This exchange was enhanced through frequent visits by Chinese nationals to Okinawa and vice-versa. It is from this foundation in Chinese martial arts, especially Fujian White Crane, that the indigenous unarmed fighting system of the Ryukyu Kingdom evolved.

For the most part, this Ryukyuan martial art – initially known as Tode (“China hand”) or simply Te (“hand”) – was practiced by members of the Pechin class, a class of feudal scholar-officials roughly equivalent to the Samurai class of Japan. In time, regionally distinct versions of the art developed and were dubbed Naha-te, Shuri-te, and Tomari-te after the towns in which they originated (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The island of Okinawa, showing the towns in which regional versions of the indigenous martial art known as “Te” developed. These became known as Naha-te, Shur-te, and Tomari-te. Goju-ryu is a descendant of Naha-te.

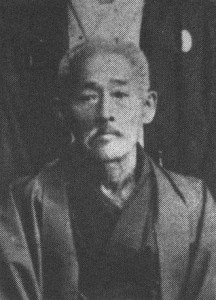

The connection with Chinese martial arts remained strong despite these local innovations, however. As a notable example, the founder of Naha-te, Kanryo Higaonna (1853-1915), spent many years training in China under Fujian White Crane master Ryū Ryū Ko before returning to Okinawa (Figure 3). Higaonna’s Naha-te was notable for its combination of hard and soft techniques and its focus on the kata Sanchin (“Three battles”), which he had learned while studying Fujian White Crane in China. Similarly, the early masters of Shuri-te and Tomari-te adapted various kata of Chinese origin as their unique Okinawan martial art continued to evolve.

Chojun Miyagi and the evolution of Goju-ryu

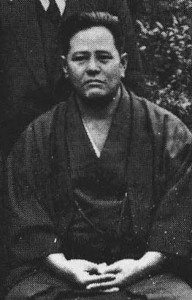

One of Kanryo Higaonna’s primary students was the young son of a wealthy shop owner in Naha named Chojun Miyagi (1888-1953) (Figure 4). Miyagi had begun training with Higaonna at the age of 14 and continued as his student until Higaonna’s death 15 years later, interrupted only by a period of military service and a trip to China to visit the grave of Ryu Ryu Ko. Miyagi returned to China a second time shortly after Higaonna’s death and spent some time training in Chinese martial arts. Upon his return to Naha, Miyagi opened a dojo and began training students. In addition to teaching the core aspects of Higaonna’s Naha-te, Miyagi continued to innovate. In the early 1920s, he created the kata Tensho (“Rotating palms”) based on forms that he had learned while in China. Miyagi considered Tensho to be a “soft” counterpart to the “hard” kata Sanchin that had been taught to him by Higaonna. He also modified Sanchin from its original Chinese form, most notably by changing the kata to use closed rather than open hands.

Just as a cultural exchange between China and the Ryukyu Kingdom involved sharing of martial arts knowledge centuries before, the Okinawan system of combat began to spread to mainland Japan in the early 20th century. In 1922, Gichin Funakoshi (a practitioner of Shuri-te and founder of the Shotokan style) travelled to Tokyo to demonstrate his art, which by then had become known as Kara-te, the kanji for which (唐手) translated as “Tang hand” or “Chinese hand”, in reference to its derivation from Chinese martial arts. Later, in the face of growing tensions between Japan and China, the kanji used for the term Kara-te was changed to 空手, meaning simply “empty hand” (but pronounced in the same way as before).

In 1929, a demonstration of various Japanese martial arts was held in Kyoto. Representatives of Okinawan karate were present, but Chojun Miyagi himself was unable to take part. One of his students, Jin’an Shinsato, attended in his place. When asked the name of his particular brand of martial arts, Shinsato had no formal name to offer as Miyagi had not yet christened his particular style. Miyagi subsequently chose the name Goju-ryu, or “hard-soft style”, to reflect the particular characteristics of the style. The name itself was taken from a line in the Hakku Kenpo (“The eight laws of the fist”), which is part of the Bubishi – a centuries-old manual of Chinese martial arts that has long been revered by many Okinawan karate masters. The precept in question, Ho wa Gōjū wa Donto su, asserts that “inhaling represents softness while exhaling represents hardness”.

The exchange between Okinawa and Japan occurred in both directions, with significant impacts on the evolution of how karate was practiced in its native Okinawa. The change in in the meaning of karate to “empty hand” is one example, but there were many other influences. Inspired by Japanese martial arts such as Kendo and Judo, Karate evolved from a largely combative art to one with an expanded emphasis on personal character development. This is reflected in the modern term “Karate-Do” – not just a system of fighting with empty hands, but of following the Do (“way” or “path”) of Karate training. Other features of modern Karate, such as the use of the dogi as the standard training uniform, the Kyu/Dan ranking system, and the implementation of coloured belts (obi) to signify level of advancement are all relatively recent imports from Judo. Chojun Miyagi, for his part, never granted Dan ranks to any of his students, although he did adopt the use of the dogi and obi.

By the 1930s, Karate training was no longer the exclusive domain of a masters and a handful of their personal students. Instead, Karate had become part of the curriculum in many schools and was adapted in various ways to fit this new audience. The combative nature of the art was further deemphasized, and additional training kata were developed. In the case of Goju-ryu, this included the kata Gekisai Ichi and Gekisai Ni, which were developed for use in schools by Chojun Miyagi in 1940. These have since been included in the standard Goju-ryu curriculum, which consists of 12 kata – many of which are of Chinese origin, adapted and modified by Higaonna, Miyagi, and their successors.

Goju-ryu after Chojun Miyagi

Along with the other major styles of Karate, Goju-ryu began to spread beyond the borders of Okinawa and Japan following World War II. In particular, many American servicemen stationed in Okinawa began to train in Karate, bringing some knowledge of the art with them when they returned home. Nevertheless, the primary home of Karate remained (and remains) Japan, and Okinawa in particular.

Beginning in the late 1920s, Chojun Miyagi taught Karate at the Okinawan police academy. He also trained a number of personal students in his “garden dojo” at home, several of whom began training under Miyagi in their early teenage years and continued as his student until his death in 1953. Following his death, it fell to these students to carry on Miyagi’s legacy of Goju-ryu. This was made somewhat challenging by the fact that Chojun Miyagi did not publically appoint any successor and very little photographic or written record exists of his specific teachings. Perhaps not surprisingly, this has led to the emergence of several distinct schools of Okinawan Goju-ryu karate, in addition to off-shoots of Okinawan Goju-ryu such as the Japanese version Goju-ryu developed and promoted by Gogen Yamaguchi.

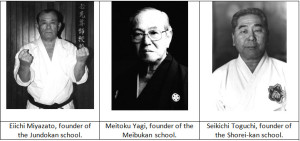

Three of Chojun Miyagi’s senior students, in particular, have played a major role in the preservation and ongoing evolution of Okinawan Goju-ryu: Meitoku Yagi (1912-2003), who founded the Meibukan school (“House of the pure-minded warrior”); Ei’ichi Miyazato (1922-1999), founder of the Jundokan school (“House in which we follow in the master’s footsteps”); and Seikichi Toguchi (1917-1998), who created the Shorei-kan school (“House of politeness and respect”) (Figure 5).

Some of these schools have, in turn, spawned descendant organizations such as the IOGKF of Morio Higaonna (a former student of Ei’ichi Miyazato) and different branches of Meibukan Goju-ryu (Figure 6).

Modern Goju-ryu

The three major schools of Goju-ryu have diverged in various ways over the intervening decades. Some of the changes relate to minor aspects of kata performance (Figure 7). There are also distinctions in the order and number of kata taught in the curricula of the different schools. For example, the Jundokan school has two versions of Sanchin, one in which the practitioner executes two 180° turns during the kata (based on Higaonna’s version), and one that is restricted to forward and backward movements only (a version developed by Miyagi). The Meibukan school features five original kata that were developed by Meitoku Yagi and differ from traditional Goju-ryu kata in a number of notable ways (especially the opening pose, chambered fist orientation, and distancing).

Figure 7. An example of minor differences in kata performance between schools of Goju-ryu. This shows the first two techniques in Gekisai Ichi. The Jundokan version (top; from Okinawa Den Gojuryu Karate-do by Ei’ichi Miyazato ) uses a high punch, whereas the Meibukan (middle; Karate Goju Ryu Meibukan by Lex Opdam) and Shorei-kan (bottom; from Okinawan Goju Ryu: The Fundamentals of Shorei-kan Karate by Seikichi Toguchi) versions use a middle punch.

It is not difficult to understand how different lineages of Goju-ryu have have diverged. Minor differences in kata performance, training regime, drills, and other elements arise even among dojos within the same organization. It is also possible that each of the founders of the major schools of Goju-ryu were taught slightly differently by Chojun Miyagi. Each may have taken away different details from common teachings as well. The important issue, it would seem, is that these schools have sought to preserve the core aspects of Goju-ryu – something that is not affected by comparatively minor deviations or differences in emphasis. That core includes a focus on the balance between hard (go) and soft (ju) techniques, a foundation built on Sanchin (and Tensho) kata, an emphasis on close-quarters fighting and efficiency of movement, and the use of circular movements that reflect Goju-ryu’s roots in Chinese martial arts. That these masters embodied the fundamental essence of Goju-ryu laid down by Chojun Miyagi is reflected by the fact that, following his death, Ei’ichi Miyazato carried on teaching at Miyagi’s “garden dojo”. A few years later, Miyagi’s family presented Meitoku Yagi with Miyagi’s gi and obi.

Notwithstanding their lifelong dedication to preserving traditional Goju-ryu as they had learned it, the founders of the major lineages of modern Goju-ryu were each masters in their own right. They all lived and trained much longer than Chojun Miyagi himself, and each has provided a unique perspective on the essence of Goju-ryu while also introducing new innovations into their respective schools.

This theme of evolution, innovation, and a preserved essence is common throughout the entire history of Goju-ryu karate. Kanryo Higaonna’s adaptation of the arts he learned in China led to the advent of Naha-te, and Chojun Miyagi’s further innovation was essential in the rise of Goju-ryu from this Naha-te foundation. Miyagi’s senior students – who became grandmasters in their turn – have carried on this legacy.

Indeed, change is as much a part of traditional Okinawan Goju-ryu as is tradition itself.

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Kodokan Judo

Kodokan Judo